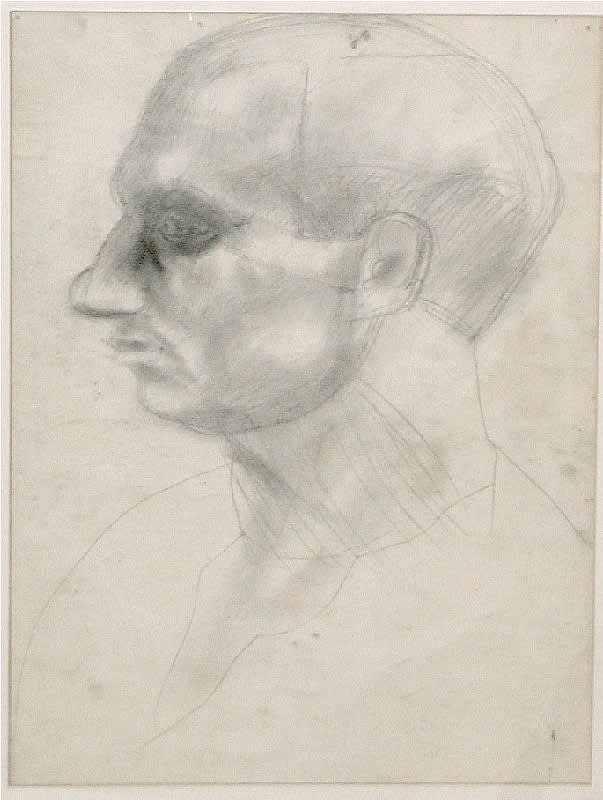

David Bomberg 1890-1957

Self Portrait, 1919

Pencil on paper

47 x 35 cms

18 8/16 x 13 12/16 ins

18 8/16 x 13 12/16 ins

1336

Sold

One of Bomberg's earliest teachers was Walter Sickert, although his work shows little evidence of any such influence. What both artists did share, however, was the centrality they gave to...

One of Bomberg's earliest teachers was Walter Sickert, although his work shows little evidence of any such influence. What both artists did share, however, was the centrality they gave to drawing as the necessary scaffolding for ever more daring painting - a legacy which would also be passed on to subsequent generations - but their differences were otherwise fundamental. Not least, Bomberg's idea of a 'spirit in the mass' introduced a spiritual and psychological dimension that is far removed from Sickert's concerns. Sickert may have explored the relationship between paired figures but seldom is individual psychology a prime concern. Instead Sickert is frequently more detached, his concerns more formal and his results often schematic. Bomberg, in contrast, often tends towards a more elemental expressionism. This difference is exemplified by these artists' self-portraits.

Whilst Sickert's occasional self-portraits tend to aggrandise the subject and to project the

desired public face of a celebrated figure, Bomberg's numerous self-portraits became increasingly raw and uncensored expressions of emotional turmoil, suggesting that they fulfilled a therapeutic function for an artist who felt isolated, embittered and possessed little sense of an audience.

The changes to Bomberg's self-imaging and the ways that this reflected his troubled life is evident from a comparison of these two self-portraits. The pencil drawing from 1919, shows the artist in profile, and is strong, assertive and robust. Despite the modelling, the outlining of the hair, the ear and the neck all suggest the abbreviating intensity of Bomberg's recent work as a Vorticist, giving a slightly machine-like feel to the head. In contrast, the later painting shows the artist emerging from the darkness and is so densely worked that it suggests an affinity with the early paintings of Auerbach and Kossoff, which is otherwise far less evident.

Whilst Sickert's occasional self-portraits tend to aggrandise the subject and to project the

desired public face of a celebrated figure, Bomberg's numerous self-portraits became increasingly raw and uncensored expressions of emotional turmoil, suggesting that they fulfilled a therapeutic function for an artist who felt isolated, embittered and possessed little sense of an audience.

The changes to Bomberg's self-imaging and the ways that this reflected his troubled life is evident from a comparison of these two self-portraits. The pencil drawing from 1919, shows the artist in profile, and is strong, assertive and robust. Despite the modelling, the outlining of the hair, the ear and the neck all suggest the abbreviating intensity of Bomberg's recent work as a Vorticist, giving a slightly machine-like feel to the head. In contrast, the later painting shows the artist emerging from the darkness and is so densely worked that it suggests an affinity with the early paintings of Auerbach and Kossoff, which is otherwise far less evident.